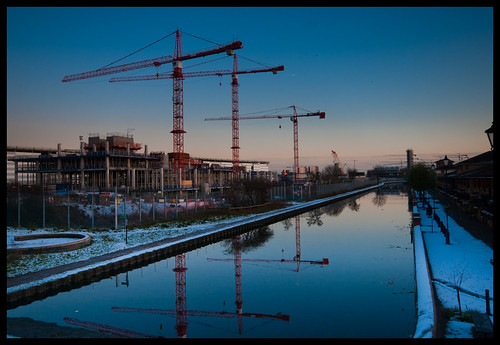

Olympic Park Cranes – Hackney, by Sam Cadby.

“Architect’s are very interesting because they’re on the brink of obsolescence…”

So saying, Iain Sinclair – psychogeographer, author, and self-nominated figure for the perpetuation of East London’s history – grouped architects with similarly defunct notions like ‘the spirit of place’, industry, integrity, common sense, community, etc, etc, etc. In short, everything that was once good and noble and is now rotten to its core. Boo, hiss, down with the modern world.

While I think the man is right about architects (I will elaborate presently), I am suspicious of anyone who would dissimulate a wild nostalgia (in which he seems veritably marinated) as a “fear of forgetting”. Certainly there is a fine line between wishing to engage meaningfully with the past and simply invoking history as a means to bombast an audience about the piteous state of the present. For me, this really distinguishes him from the other great psychogeographical author of our time, Will Self. Unlike Sinclair, Self is no moral pedagogue…

Sinclair’s subject was East London, its history, its architecture – a rose-tinted people fighting the good fight against the idiot developers and villainous politicians. In black and white terms he outlined the clear superiority of the city “as a human entity, as an organic entity” over the “post-architecture” imposed on the East by the coming Olympic-scale fuck-up. While I found his tone vaguely self-righteous, I nonetheless found his content interesting and his arguments extremely convincing (in several cases indisputable).

Readers from outside of London may not be aware of the Olympic situation, in a nutshell: the site is a vast tract of ex heavy-industrial land falling between Stratford and Hackney Wick (think fairly far east), towards the lower end of the Lea Valley (a rambling and beautiful wildlife park composed of marshes and canals). As Sinclair noted, it has always been thought of as an ‘edge’ of London – and it is psychologically disturbing to now realise that Stratford’s development will turn the nature reserve into an island, besieged by an ocean of urban nightmare.

The site beforehand, subject of the pamphlet referred to in this post on Cedric Price, was littered with industrial ruins, leftovers from a time when London still manufactured on any appreciable scale. What I did not know is that over 12,000t of radioactive material has been retrieved and re-buried at the site (evidence of a business that made glow-in-the-dark watch dials during the 60’s).

Like all Olympic games there has been scandal: £40million of “missing” funds, cost (and corner) cutting measures abound– the UK is in full recession mode after all. And yet the ridiculous promise of the developers is that they are attempting to give back a park to the public realm. This debased simulation of the wild beauty that existed before is indicative of modern ‘regeneration’ methods (e.g. an artistic drinking-hole is demolished to make way for an art-themed hotel, as at Old Street).

It would be hard to overstate either the incompetence of the architects or the stupidity of the clients involved in this venture. I’m not even going to touch that sensitive subject in this post, but simply let history validate my words. Sinclair could not find words to describe the process by which the client approaches an architect in the same way they would a hairdresser or a plastic surgeon, saying, “yeah, I like it, but I want a bit more of a curve over here – hey presto!”

Two final points, I had intended to write a short post, but the subject really fires me up:

was recently told that a town hall in Stratford was demolished in order to make way for a Tesco’s supermarket. I am now shocked to discover from Sinclair that there is a plan to extend the site to include apartments – residential zoning as an appendage to commerce: the possibility of perpetually living inside a mall. What then, mused Sinclair, is to stop all of Hackney from becoming an inner suburb of a supermarket?

the architect, that figure in decline, no longer has any control over the built environment, then what is his domain? This observation is not at all unique to Sinclair, and it is obvious that the profession is approaching a critical turning point. I would argue what we have to salvage is an architectural mode of thinking, a way of looking laterally at problems (the solutions to which often do not include buildings). The role of this coming generation of architects is to convincingly establish their dominance as the only and supreme profession of holistic thinkers… or else face professional extinction.

Hi Jack,

ReplyDeleteDoes this refer to the 'Restless Cities' event? I was disappointed to have missed it. Having a background in philosophy rather than architecture I'm wondering whether what you are suggesting is that architects should become philosophers..."holistic thinkers". I need to re-read it but Henri Lefebvre considers something along these lines in his essay 'Right to the City'.

We have to be careful though, both architects and philosophers can end up saying very silly things when they start believing they can speak for the other. Hence I'd contest whether architects should assume any kind of "dominance". Rather, architects need to be politicised. One way to achieve this is by critique. After all, with regard to Urbanism, why should architects and planners have all the fun?

I was glad you returned to the subject of psychogeography. Part of the reason for my curiosity with regard to your 'Digital Dialectic' was that it seemed to undermine both your own interest in psychogeography and some of the premises informing my own attempts to develop a critical urbanism.

I'm riveted!